“They have strong stomachs, these politicians, making the public believe that charity is a good substitute for their own betrayal. […] At the latest bazaar they bought soft linen towels for 4.50 kr per piece, hand-made by the intellectually disabled. A bargain! Cheap labor! If I had the time and money, I would take the City of Oslo to the European Court of Justice.”

With statements like the above, the Norwegian journalist and filmmaker Arne Skouen set an avalanche in motion. In the two article series “Those Who Fall Outside” and Those Who Betray Them (1965) and Situation of the Feeble-Minded (1968), both published by newspaper Dagbladet, as well as the much-noticed book Justice for the Handicapped (1966), Skouen gave a scathing judgment of the care system and social treatment of persons with intellectual and mental disabilities in Norway: They were met with either aversion or paternalistic benevolence, and if they could get access to public services at all, were accommodated in isolated and badly equipped institutions. Instead of living up to their responsibility and changing this situation, politicians would rather promote private donations and bazaars – a situation not only he found intolerable.

What form did these charity and fundraising campaigns for persons with disabilities take, at a time when the Nordic welfare states prospered? And what was so ambivalent about them that disability activists like Arne Skouen even threatened to take public authorities to court? A look at two such campaigns in the 1960s gives us some answers to these questions.

Arne Skouen with daughter Synne in 1965. Image: Norsk biografisk leksikon/NTB Scanpix

One of the first Nordic donation shows with disability as a topic was the Swedish MS-aktionen in 1959. Initiated by Neuroförbundet, an organization for persons with multiple sclerosis and other neurological disorders, the goal was to build an independent care home as an alternative to public institutions. The campaign was broadcast on public radio and it was not only financially a success, but also drew largely positive feedback both from the audience and the disability community.

MS-aktionen in 1959 was the first public charity campaign for persons with disabilities on Swedish public radio. One year later De Vanföras Väl organized Handikapp 60, here with a street collection in Sundsvall. Images: Neurologiskt Handikappades Riksförbunds arkiv, Swedish National Archive: SE/RA/730646/L/L 3/1; Norrlandsbild/Tommy Wiberg, Sundsvalls museum.

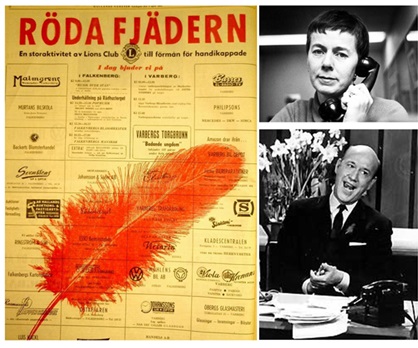

Much more critical were the reactions to the following disability campaign in 1965. Röda fädern, the Red Feather, was the first Nordic charity gala that made it to public television. Again the idea came from a Swedish disability organization, and again it was about housing. A few years before, Sven-Olof Brattgård, a doctor and wheelchair user, had developed the concept of the so-called Fokus houses, accessible and centrally located apartments where persons with disabilities could live independently with support of an in-house service (boendeservice). Together with Lions Club, the Fokus foundation approached public broadcaster SVT with the idea for a fundraising show. Röda fjädern took place in 1965, hosted by the popular TV show presenter Lennart Hyland and the journalist Lis Asklund, who a few years before had caused quite a stir among the Swedish public with an investigative radio documentation on disabled children in institutions. Röda fjädern took the audience in a storm, with over one million people watching and 11 (today ca. 110) million SEK being donated, enough to build not just one, but fourteen Fokus houses.

But not everyone was a wholehearted supporter. Especially critical was Vilhelm Ekensteen, himself a wheelchair user, visually impaired, and author of the influential book In the Backyard of the People’s Home (1968), who like Arne Skouen in Norway openly rejected donations, as “charity has never made an attempt to tear down the walls around the handicapped. […] The issue of equality never arises, when everything is set straight and the best is done, the handicapped are supposed to be good and show satisfaction, and that’s it.”

Other critics even turned against the concept of the Fokus houses themselves, seeing them as just another form of segregation. Mats Denkert from the Swedish Association for Mobility Impaired (DHR) wrote in the organization’s magazine: “DHR’s advocacy efforts against institutions has begun to yield results, and now the Fokus houses are making a one-off measure that solves all needs within the house and thus establishes new institutions.”

Journalist Lis Asklund and TV presenter Lennart Hyland hosted the Red Feather campaign on Swedish television in 1965. Images: Hallands Nyheter; Sveriges Radio; Lions Club.

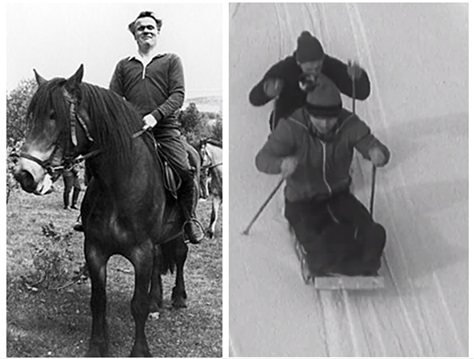

Only one year after Röda fjädern, in 1966, Norway held its first televised disability gala. Standing behind the campaign was Erling Stordahl, a blind singer known for organizing outdoor sports events for persons with disabilities. After the success of Ridderrennet, a ski competition for visually impaired people, he dreamed of opening a Disability Health Sports Centre at Beitostølen that combined physical rehabilitation with nature experiences – convinced that persons with disabilities had a right to an active social life, including culture, sports and the outdoors.

Again, the campaign was a great success: 8,6 million (today ca. 96 million) NOK were raised and Beitostølen was opened by crown prince Harald in 1970. But critique followed suit, peaking in Skouen’s article series Situation of the Feeble-Minded in 1968 in which he condemned the campaign as a mere begging for money that completely ignored discussions on rights and political responsibility. Stordahl was at the center of his disapproval: “Imagine if a man like Erling Stordahl had set his mind on [justice]. Disability is so diverse, he himself is blind. He is also eloquent and known throughout the country. What a giant he could have become in the struggle for unfortunate fellow citizens, for their dignity, for their statutory rights, for their integration into the Norwegian social policy debate. He has instead chosen to be Norway’s most virtuous beggar.”

Erling Stordahl initiated the first disability gala on Norwegian television in 1966, raising money for the construction of Beitostølen Health Sports Centre. Images: Wikimedia Commons; NRK.

Such arguments did not stop Erling Stordahl and others from organizing similar campaigns, either on television or more traditionally on the streets. They did, however, add an important dimension to the relationship between disability and society. Who was responsible for the care and well-being of persons with disabilities? How could their equal rights be ensured, and what was the role of the public in this? These questions continue to be relevant even today.

But despite the important critique from the disability community, the charity campaigns in the 1960s also had their merits. The idea behind the Fokus houses and Stordahl’s use of the Norwegian passion for sports and the outdoors resonated well with the public, while bringing positive and informative images of disability directly into people’s living rooms. Contrary to what has often been criticized about donation galas in other countries like the United States, persons with disabilities were seldom depicted as suffering and in dire need of help. The collected money was less intended as a substitute for welfare than as a means for realizing novel and innovative projects.

Donation galas remain popular in the Nordic countries. Good examples are TV-aksjonen in Norway and Musikhjälpen in Sweden, two shows that repeatedly have disability as a topic. Unlike the 1960s, however, they are no longer collecting for the benefit of local disability organizations but have shifted their support to poor and underdeveloped countries, with a strong focus on equality and rights.

Sources and further readings:

- En röd fjäder engagerade svenskarna, Hallands Nyheter03.2015.

- NRK: Beitostølen – hvor funksjonshemmede mobiliserer ubrukte krefter, 17.09.1976 (film)

- NRK: Norsk portrett – Erling Stordahl, 24.12.1970 (film)

- Skouen, Arne: articles in Dagbladet, 1965-1968, in: Uhørte stemmer og glemte steder: fortellinger fra utviklingshemmedes historie (link)

- Syse, Aslak: Rettighetsforkjemperen, Dagbladet07.2008.

- Thelander, Anne; Månsson, Karin; Winberg, Peter: NHR 50 år, 1957-2007, Neurologiskt Handikappades Riksförbund, Stockholm 2009.

- Wallsten, Anna: Röda fjädern och fokushusen. En boendes berättelse. Stiftelsen Nordiska Museet / HAIKU-projektet, 2013.

- Wermeling, Erika: Stiftelsen Fokus, 08.02.2016 (link)