It’s just after 6 in the evening and the Erasmus University is slowly getting empty, when a group of about 10 students and PhD’s from psychology, neurobiology and even economics gather in a small lecture hall for a meeting of the Psychedelic Science Collective Rotterdam about ‘MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for PTSD’. The Psychedelic Science Collective Rotterdam is one of several organizations in the Netherlands, as for instance the Amsterdam Psychedelic Research Association – APRA, that since a few years have started to organize events to ‘inform people about the research into psychedelics and their application in medicine’, as well as lobby for the ‘destigmatization of psychedelic substance’. Starting out from the working of psychedelic drugs in for instance psychotherapy, they rethink how we can understand mental disorders as PTSD and make the already existing treatments more effective.

Whereas the Dutch Psychedelic Science Collectives are just beginning to organize, in the United States the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies America or MAPS has since the 1980s lobbied for awareness of the potential beneficial use of psychedelics in psychotherapy and funded trials with psychedelic substances as MDMA (3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine) in psychotherapy. One of the first clinical trials that MAPS funded was a Spanish study on MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for victims of sexual abuse who suffered from PTSD that began in 2000 but ended two years later due to political pressure.[1] Since large pharmaceutical companies remain thus far sceptical and arguably wary of changing political views and regulations regarding the use of psychedelics, MAPS has entirely funded the only three therapeutic phase-two trials that have currently been conducted.[2]

As one of the in Rotterdam present PhD-students fittingly explains the reason that MDMA was chosen for these trials was not just because it, more so then other psychedelics, helps creating a bound of trust between patient and psychiatrist. An important factor was indeed that ‘MDMA in America at least, simply has not the same negative connotations as LSD as it is not related to counter-culture or hippies in any way’.[3] That made the trials politically less sensitive, as the 2016 approval of phase 3 trials by the FDA De Food and Drug Administration proves.[4] The expectations are that these clinical trials in the United States, Canada and Israel will be concluded somewhere in 2021 and that the first MDMA-assisted psychotherapy will be available in Europe within a few years as well.[5]

Picture from the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies TNS

Whereas research on psychedelic substances as MDMA in psychiatry already started in the 1950s, this became politically controversial and was eventually banned in the early 1970s in reaction to the recreation use of especially LSD.[6] Since the late 1990s, MDMA-assisted psychotherapy is however in growing interest again due to a number of reasons. First, the Decade of the Brain that was launched by president Bush in the 1990s, stimulated a renewed scientific and political interest in the neurobiological functioning of the brain in mental disorders. Secondly, the fact that ‘major pharmaceutical companies that formerly pursued aggressive and very expensive research in this field have withdrawn because of the high rate of failure to find medications’, there is a need for new treatment options for the rising costs of mental healthcare and thirdly there is a growing frustration among psychiatrists and psychologist with the lack of success of existing treatment options.[7]

The convincing success of the initial trials that were conducted with MDMA-assisted psychotherapy further contribute to the current widespread scientific and public optimism in the possibilities that psychedelics offer.[8] Considering that the trials that have been conducted thus far almost always focussed on group of individuals with ‘chronic PTSD’, so-called because other forms of therapy and medication (both pharmacotherapies and psychotherapies) did not help, adds to the optimism on MDMA-assisted therapy.[9] Studies of for instance Mithoefer (2011, 2013, 2018) showed that after MDMA-assisted psychotherapy 83% of the participants stopped showing any symptoms of PTSD and the Phase II trial of MAPS in Canada that were concluded in 2016, showed as well that 68% of the participants no longer had any of the PTSD related symptoms.[10] Follow-up studies after 3.5 years additionally showed that these results were enduring over a longer period of time as well.[11]

‘Eliminating symptoms entirely would be a huge breakthrough, as PSTD is notoriously difficult to treat. With PTSD the traumatic memory of the incident replays like a tape loop in the patient’s mind. MDMA doesn’t eliminate the traumatic memory, but it takes away the emotional impact so that the memory no longer controls a person’

– Mark Haden, professor at the University of British Columbia’s School of Population and Public Health. [13]

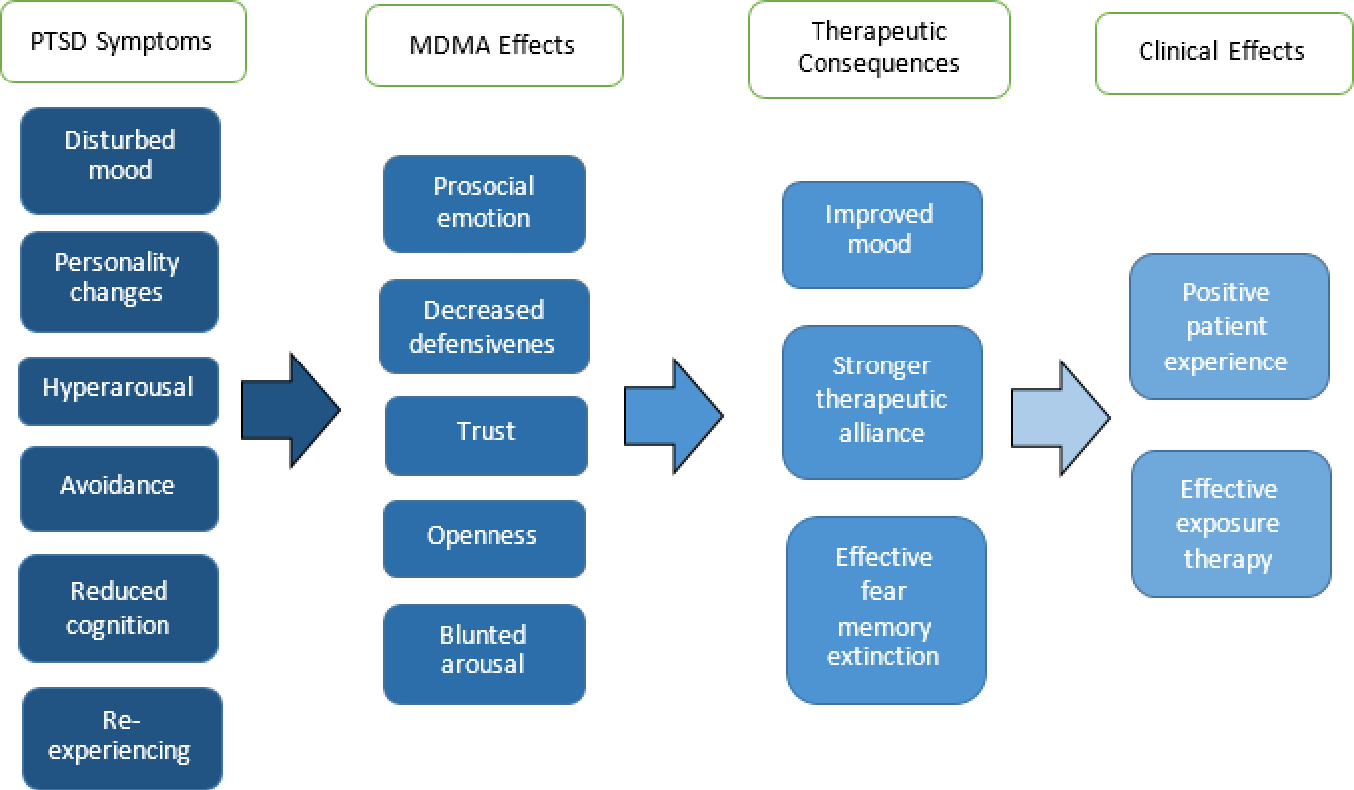

What makes the MDMA assisted psychotherapy revolutionary as well is that the ‘assistance’ of MDMA allows for a ‘mainly non-directive, patient-driven method by emphasizing empathetic presence and listening and non-directive communication’.[14] This primarily comes from the fact that MDMA causes a ‘detachment from the feeling of imminent threat’, an ‘noticeable inherent feeling of safety’ and ‘accelerated emotional processing’, while at the same time it still allows people to ‘access and confront traumatic memories’. The current MAPS manual on MDMA-assisted psychotherapy only takes into account two to three sessions of 6 to 8 hours, usually 2 to 6 weeks apart, where MDMA is used in assistance, while the total treatment period ‘usually’ includes around 15 sessions. This makes it significant shorter then usually therapeutic treatments of PTSD and possibly, over time, less-expensive as well.[15] With two psychologists, a male and female, being present on ‘either side of the patient’, the aim of these sessions is for the ‘the contents of the trauma to erupt spontaneously’, while the patient is able to reflect and verbalize their ‘experience’ in later sessions or when the ‘peak effects of MDMA’ go away. Although the dose of MDMA differentiates between studies, the MAPS manual considers 125 mg as a ‘full dose’, but other doses that have been used in trials are sometimes as ‘low’ as 30 mg, making the doses in trials significantly less than the 200 to 250 mg MDMA usage that is common in party circuit.

Picture from the handout of MAPS

Rethinking PTSD and its treatment through the appliance of MDMA.

While personal experiences with both MDMA as therapy shape at least an part of the meeting of the Psychedelic Collective, the central focus was a recent qualitative study on the effects of the MDMA-assistant treatment that was conducted in 2019 by Barone, W., Beck, J., Mitsunaga-Whitten et al.[16] The clinical trials that were described above used the so-called Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS-IV) to measure the outcomes in how much the frequency and intensity of PTSD symptoms were reduced, the authors of this qualitative study argue that this alone ‘cannot measure changes in essential areas that supplant a diagnosis of PTSD or arise alongside symptoms’. The 19 people with chronical PTSD that they interviewed took part in the phase 2 clinical trial that found ‘significant and durable reductions in PTSD symptoms that persist more than one year following the treatment’. Besides symptom reduction however, these interviews showed how the participants described a further improvement on ‘self-awareness’, ‘relationships and social skills’ and ‘openness to continued therapy’.

This is especially interesting for it gives new insights in how these individuals with PTSD perceive the effects, beyond the direct symptoms, of PTSD. All participants note that the treatment effectively ‘altered their perception of self and brought about more self-compassion’. One participant described how the MDMA-assistance allowed him to ‘see yourself like you can read a book and see everything that you stand for and kind of analyse your own self, your own thought and reasoning’. Another participant noted that the treatment helped to ‘communicate what I’m going through’ while before she was ‘never able to communicate with anybody about any of the issues’. Another participant said that the MDMA let her fell as if ‘I was capable and safe of tackling the issues. Whereas before I feared those thoughts and I tried to avoid them at all times, and avoid things that reminded me of those thoughts, I think it allowed me to feel safe in my space’. Finally, a participant notes that the MDMA-assistance helped making her or him more open to therapy in general. ‘I had a lot of defences going up into the therapies that I had previous to the MDMA, and it made accomplishing any breakthroughs impossible. With MDMA, it broke this hard, outer shell that was up that kept me from being able to connect with the therapies I was going through.’

Model of how PTSD contributes in psychotherapy

Whereas the study concludes that a ‘common factor among participants was the belief that this treatment provided them healing beyond what they could find in traditional modalities’, these trials in itself could be used to reflect on the ‘traditional’ treatments of PTSD as well. As one of the participants in the meeting notes, ‘the point is as well that this shows what kinds of effects the participants report, are these effects the result of the appliance of MDMA or are these simply things that are useful for people with PTSD?’ The fact that the participants in this qualitative study focus so much on how the MDMA-assisted therapy helped them ‘strengthen their self-awareness and self-acceptance’ and especially helped them improve their functioning in social activities and relationships, might as well mean that these are simply important factors people with PTSD struggle with beyond the direct, already well known, symptoms. This means that the results of these MDMA-assisted psychotherapy trials could not just help rethink what exactly PTSD is beyond its direct well-known symptoms, but also revaluate existing therapies and see if ‘there are different ways then the MDMA-assisted psychotherapy to help people with PTSD get this self-awareness and improved functioning in social relationships’.

[1] d’Otalora, M., ‘MDMA and LSD therapy in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder in a case of sexual abuse’, in: Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (2004) and Bouso, J.C., ‘MDMA/PTSD research in Spain. An update’, in: MAPS Bulletin 13 (1) (2003) 7–8.

[2] Bouso, J.C.; Doblin, R.; Farre, M.; Alcazar, M.A. & Gomez-Jarabo, G., ‘MDMA-assisted psychotherapy using low doses in a small sample of women with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder’, in: Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 40 (3) (2008) 225–36.

[3] The Lancet, Reviving research into psychedelic drugs. Lancet 367, (2006) 1214.

[4] Thal, S. B., & Lommen, M. J. J., ‘Current Perspective on MDMA-Assisted Psychotherapy for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder’, in: Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy 48(2) (2018) 99-108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-017-9379-2

[5] Maps, ‘A Phase 3 Program of MDMA-Assisted Psychotherapy for the Treatment of Severe Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)’ https://maps.org/research/mdma/ptsd/phase3

[6] Sean J. Belouin, Jack E. Henningfield, ‘Psychedelics. Where we are now, why we got here, what we must do’, Neuropharmacology Nov 142:7-19 (2018) 9.

[7] Sean J. Belouin, Jack E. Henningfield, ‘Psychedelics. Where we are now, why we got here, what we must do’, Neuropharmacology Nov 142:7-19 (2018) 9.

[8] World Health Organization, ‘Mental Health Action Plan 2013-2020. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland’ (2013).

[9] Mithoefer et al. ‘3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)-assisted psychotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder in military veterans, firefighters, and police officers: a randomised, fulltextouble-blind, dose-response, phase 2 clinical trial’, in: The Lancet, online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30135-4 (2018).Mithoefer, M.C., Wagner, M.T., Mithoefer, A. T., Jerome, L., & Doblin, R., ‘The safety and efficacy of ±3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine-assisted psychotherapy in subjects with chronic, treatment-resistant posttraumatic stress disorder: the first randomized controlled pilot study’, in: Journal of Psychopharmacology 25(4): 439–452. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3122379/

[10] https://mapscanada.org/research/mdma-for-ptsd-phase-2

[11] VGCT, ‘Trippen op MDMA bij de psycholoog’ (2018). https://www.vgct.nl/themas/trauma/-ptss/trippen-op-mdma-bij-de-psycholoog

[12] Banks, K., ‘The Canadian revival of psychedelic drug research’, in: University Affairs (june 2019) https://www.universityaffairs.ca/features/feature-article/the-canadian-revival-of-psychedelic-drug-research/

[13] Banks, K., ‘The Canadian revival of psychedelic drug research’, in: University Affairs (june 2019)

[14] Thal, S. B., & Lommen, M. J. J., Current Perspective on MDMA-Assisted Psychotherapy for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 48(2) (2018) 99-108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-017-9379-2

[15] Emerson, A., Ponté, L., Jerome, L., & Doblin, R. History and future of the multidisciplinary association for psychedelic studies (MAPS). Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 46.1 (2014) 27–36.

[16] Barone, W., Beck, J., Mitsunaga-Whitten, M., Perl, P. ‘Perceived Benefits of MDMA-Assisted Psychotherapy beyond Symptom Reduction. Qualitative Follow-Up Study of a Clinical Trial for Individuals with Treatment-Resistant PTSD’, in: J Psychoactive Drugs april-june (2019) 199-208.