In the year 1979, millions of Egyptians mesmerized in front of their television sets watching a TV series about the life of a blind man from a subaltern village in Upper Egypt who fought against poverty, ignorance and illness to become a symbol of enlightenment in post colonial Egypt. The Egyptian state television aired the series that was based on the autobiography of Taha Hussein while Egypt was getting ready to participate in the International Year of Disabled Persons in 1981.

Taha Hussein for most Egyptians is simply a voice of our own. His legacy does not stop on his struggle against blindness; he was born to a poor family in one of the least privileged territories of Egypt. His family sent him to a small local Quran school then to AlAzhar hoping that one day he could make a living by reciting Quran in social occasions or to be a teacher at the best to think of.

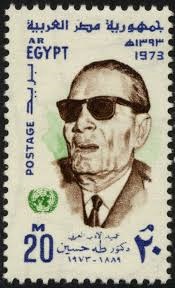

It is very common that Egyptian parents give their children an example of Dr Taha Hussein; a poor boy born in 1889 who became the first to hold a PhD degree from Cairo University. After a vicious fight with his conservative educators, Hussein was awarded scholarship and obtained a second PhD degree from the Sorbonne in 1919. Egyptian mothers always put Hussein’s story in front of their children to remind them that disability, economic hardship and even social and economic injustice are not accepted excuses for failure.

Public education in Egypt is preserving the legacy of Hussein as much as parents do. Students are taught in all pre-University grades his biography, short stories, articles or quotes in the curricula of Arabic and or Egyptian modern history. During their senior last year in secondary education, Egyptian students study a simplified version of Hussein’s autobiography AlAyam (The Days), on which the TV series was based. Whenever a new project or facility is established in Egypt to support the blind society his name comes first. From the prestigious special library of Taha Hussein which is part of the Bibliotheca Alexandrina to the small special schools in Nile Delta.

Hussein was never away from students or education until his death in 1973. When he became a minister of Ma’aref, currently education and culture, he issued a ministerial decree in 1951 to abolish all fees in all public and vocational secondary schools. Earlier in 1944 he served as a consultant to the minister of education, who implemented Hussein’s recommendation of abolishing primary education fees. Eighteen million Egyptian students are enrolled in free public schools today thanks to Taha Hussein who believed that the cost of education was the biggest obstacle hindering Egyptian families from sending young boys and girls to schools. His famous quote “education is a right as water and air” is clearly written and raised on schools and university walls as well as the back covers of school books.

His disability was never a savior out of his literary and intellectual fights in time when Egypt was witnessing major changes. While the social and cultural life in Egypt was thriving between conservatism and modernization, Hussein was there fighting from the time of the Great War to the early seventies. He never minded a battle nor tried to use his disability as a justification or escape from his rivals’ attacks. When the most famous cinema producer Mrs. Aziza Amir tried to acquire the intellectual rights of his novels in order to produce them as films, Hussein insisted to add a contract condition that he can interfere in the director’s vision of the scenario and the dialogue whenever he felt that his novel is being transformed into a story he did not mean. A condition that a director would not accept from a man who is capable of seeing and judging the imagery of his film. Mrs Amir knowing that Hussein has enough imagination to see, by his heart and mind, approved the condition.

His blindness did not save him from being accused of blasphemy and heresy which eventually led to his termination of being the dean of Cairo University’s faculty of Arts in 1932. Hussein wrote his most controversial book Fi Alsher Algaheli (Pre-Islam Poetry) questioning the whole methodology and construction of pre-Islam Arabic poetry and literary history. He even accused Arab and Islamic linguists and historians of faking, or at least accepting a fake, history for Arab tribes before Islam. He stood in court for trial and was fired from his deanship position for questioning a taboo and trying to reach for an issue that all Arab and Muslim intellectuals avoided for centuries knowing that what happened to Hussein or even worse would have happened to them.

Being a person with a disability did not save Hussein neither from blasphemy nor Zionism accusation. All his life, Taha Hussein was a lecturer in Egyptian universities. However, occupying posts as a dean of Arts, Rector of Alexandria University or as a minister for education was merely a political decision. The only time he was called by his disability was in 1950 when a group of Cairo university students gathered to protest a decision of his; and chanted “down with the blind minister”. Hussein replied that he thanks God who blinded him so that he won’t see those ugly faces. It was one of those rare occasions where Hussein was called “blind” in a political or intellectual debate. Yet it was the most hurtful as it came out from students he gave his life to educate.

Despite the massive change of the political and social Egyptian scene after the 1952 revolution, Hussein’s status and respect in the governing circles did not change. Though he was no longer a minister, the new regime used the voice and example of Hussein to support the new slogans of a socialist and nationalist Egypt where the descendants of Egyptian peasants are capable of leading the new Egypt. Numerous faces of politics, business, journalism and culture were considered symbols of an era that ended and they must end with. Hussein was one of the faces that would support the new agenda and perfectly represents its vision. Hussein had his ups and downs with the new rulers. Due to his critical comments on the writings of president Gamal Abd Elnasser in 1964, he was again fired from his position as chief editor of Al Gomhuryea newspaper, the mouthpiece of the new regime. He was later decorated with the “Necklace of the Nile” the highest civilian Egyptian decoration in 1965. An act that sounded like an apology yet it was a step the regime could not ignore while drawing itself progressive and respectful to the great minds of the nation.

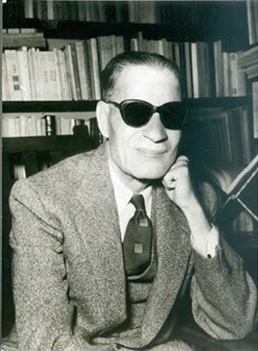

The most striking element of the legacy of Taha Hussein will always be how his disability became irrelevant to the limit where his intellectual and political rivals ignored it and did not refrain from confronting him, feeling sympathy or taking it softly with a “blind man”. It is worth noticing how Hussein forced his enemies to see him as a man strong enough to fight against. If it was not for his iconic picture with his eyes hidden behind his black glasses, we would have only remembered an Egyptian man paving his own road from a village in Upper Egypt to the Sorbonne in the 1st quarter of the 20th century.

For common Egyptians who watched TV series and read school books Hussein is a man who defeated poverty and blindness. For Arab intelligentsia he is the dean who took part in enlightening a whole nation despite being impaired from seeing the light.

Thank you for sharing