Samuel Brady is a Ph.D. student at the University of Glasgow. Having just begun a studentship researching the socio-political and technical history of the sports wheelchair in collaboration with the National Paralympic Heritage Trust, he has a deep interest in disability history, as well as matters of intersectionality, and as such all his major research projects have focused on these topics. For example, he conducted research into disability in the early 20th Century Jewish community of Leeds for his Masters degree as well as research into disability in the politics and literature of the Harlem Renaissance for his Undergraduate degree, both at the University of Leeds. As a Jewish person with a learning impairment, he believes talking about disability in the Jewish community is an important step towards a more inclusive community.

This blog is part of our crowdsourcing initiative in which we asked the public to contribute their knowledge about the impact of the International Year of Disabled Persons through blogposts. For more information see: https://rethinkingdisability.net/call-for-blogposts/

British Jews and the International Year of Disabled people

In the 17th October 1980 issue of the Jewish Chronicle, a letter from a female, wheelchair-using Jewish member of the Multiple Sclerosis Society detailed her difficulties attending synagogue during Rosh Hashana, the Jewish New Year.[1] Upon arrival at the Egerton Road Synagogue, she and her husband found no way for her to access the women’s portion of the prayer chamber. In Orthodox Jewish tradition, men and women sit separately, often with female congregants sitting in a gallery one floor above the men. At this Synagogue, the ladies’ gallery was only accessible by staircase, giving her no access options. When they asked if she could simply remain in the wheelchair at the back of the prayer chamber, they were refused and offered the alternative of remaining in the foyer, next to an open door, so she could still hear the religious proceedings. Alone, this letter could highlight issues surrounding physical access in synagogues, or the intersections between gender and disability for disabled Jewish women. However, replies to this letter place it within the context of the International Year of Disabled People (IYDP) and tells us much about how disability was treated in the Anglo-Jewish community in this period.

A reply two weeks later was shocked at this case, given the writer’s anecdotal view that synagogues across the denominational spectrum were “sympathetic” to the needs of others.[2] They went on to invoke the aims of the upcoming International Year of Disabled people to stress the change which was needed in the community:

- The increasing awareness of the needs, abilities, and aspirations of disabled people.

- The participation, equality, and integration of disabled people.

- The prevention of disability.

- More positive attitudes towards disabled people.

The second reply – penned by the secretary of the synagogue – suggested however that this situation was caused by a lack of forward correspondence by the disabled person in question, and that there was an appropriate viewing area, but this was inaccessible for safety reasons that were insurmountable on the day.[3] This second response, in certain ways, encapsulates the need for a broad, large-scale movement like the IYDP, and the importance of awareness about disability in the Jewish community.

The Anglo-Jewish community had established various forms of social welfare since readmission in the mid-seventeenth century, and this allowed the community to support itself in times of struggle. Frankel advances this idea, by suggesting that Jewish welfare is “inextricably linked to the survival and maintenance of Jewish values and a Jewish presence in the Diaspora.”[4] Jewish welfare usually took the form of financial support, however, such as providing loans to help unestablished immigrants set up small businesses, or providing money for specific religious foods, although there was occasional support for disabled people. Nonetheless, disabled Jews have often found themselves distanced from the wider community, and Jews admitted to non-Jewish institutions and asylums were frequently completely divorced from their Jewish cultural and religious life.[5] Thankfully, attitudes towards disability in the community began to change after the Second World War, and Jewish disabled people were offered more support via organizations dedicated to certain impairments, such as the Jewish Deaf Association and the Jewish Blind and Physically Handicapped Society. These groups allowed disabled Jews to retain their Jewish identities whilst receiving dedicated care and support, eliminating many issues of the existing support systems. Nevertheless, these systems were not perfect, and the advent of the IYDP encouraged further consideration of the lives of disabled Jews.

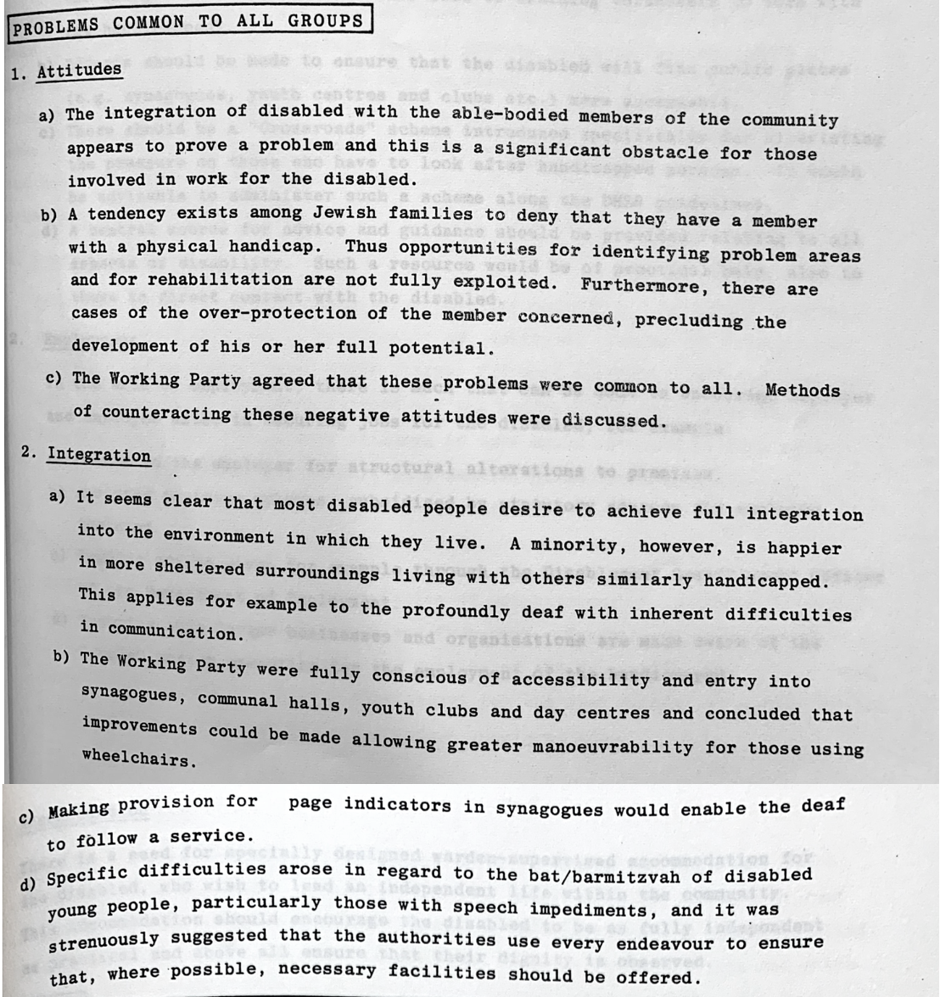

The Central Council for Jewish Social Service, created in the 1970s, sought to improve the ways in which Jewish social care operated, by introducing a unified system of co-ordination and improved service delivery of social care within these organizations.[6] As part of this aim, the Council wished to review the various Jewish disabled care organizations which fell under its remit and see how they could improve its service based on the aims of the IYDP. A sub-committee was formed of representatives from the Office of the Chief Rabbi, the Jewish Blind Society, Young Jewish Disabled and the Jewish Deaf society, among others. Their goal was to identify issues faced by disabled Jews in the community, make recommendations of how existing services and facilities could be improved, and consider the attitudes of the wider Jewish community towards disability.[7] Importantly, this research only extended to those with sensory or physical impairments, as another committee examined problems related to mental illnesses, psychological impairments and learning difficulties (evidence of which I was unfortunately unable to find). Upon reviewing existing resources and facilities, and conducting research into those Jews with specific impairments, the Committee agreed to two key areas of improvement, as demonstrated in the following image:

The scan of the above report findings is included with the permission of the Office of the Chief Rabbi and the London Metropolitan Archive.

The ways in which the committee recommended to solve these issues largely related to better education for non-disabled people in the community about disabled people, via better training for rabbis, teachers, and youth leaders; encouraging school and youth movement to engage more with disabled people; and the creation of initiatives by synagogues to better educate congregants. Other recommendations specified the need for separate residential facilities for deaf Jews; better accessibility from residences into Jewish neighborhoods, shops and places of worship; and more encouragement of independence in all walks of life.[8] The message from the committee’s findings is clear: residential facilities needed to be more accessible and more encouraging of independent living, whilst also recognizing that many barriers facing disabled Jews came from non-disabled Jews, and using education to improve this. Vitally, these recommendations fall in line with the mission of the IYDP; increasing participation of disabled people, spreading awareness and creating positive attitudes in the wider population. Importantly, the committee recognized the long-term support that would be needed to make these changes:

“Although the incentive to establish the Advisory committee was designed to mark the International Year of Disabled People, it is felt that in keeping with one of the major aims of the year, such a project should not be terminated with a report at the end of 1981. But the work commenced during the Year should be considered as a springboard for future developments…”.[9]

Disappointingly, however, it does not seem like much immediate improvement beyond the report was achieved in 1981. In a letter sent to the Office of the Chief Rabbi on 31st December 1981, the last day of the IYDP, mention is only made of one specific development; occasional prayer services specifically for deaf Jews.[10] This makes sense, as the report highlights large scale issues in the community and the recommendations would be unfeasible to introduce within the year itself. Yet, negative attitudes toward disabled people and impairment could still be easily found in 1981. One such example is in reference to then Chief Rabbi Immanuel Jakobovits, who in November 1981 wrote about the Jewish duty to preserve life. Whilst starting his argument with maxim of spiritual equality regardless of physical or psychological impairment, Jakobovits argues that under no-circumstances is ‘quality of life’ sufficient justification for the deliberate ending a life. To further this point, he comments: “the tragedy of a defective child may open up otherwise inaccessible resources of selfless love and other spiritual virtues. The supreme objective value of a cruelly afflicted being may well lie in the refining influences such as life exercises on those charged tenderly to protect it.”[11] This argument objectifies the disabled person, by reducing them to a means to a spiritual end, while invoking negative language such as ‘tragedy’ and ‘cruelly afflicted’, which are often associated with a medicalized view of disability. As such, the need for more education for spiritual and community leaders was of great importance for the future inclusion of disabled Jews, as highlighted by the subcommittee’s findings.

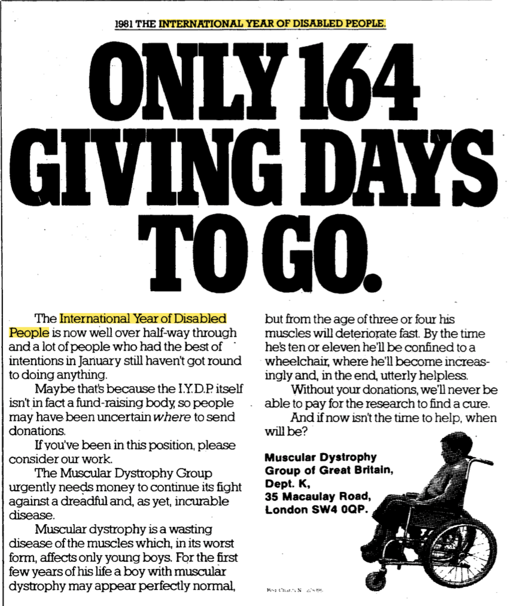

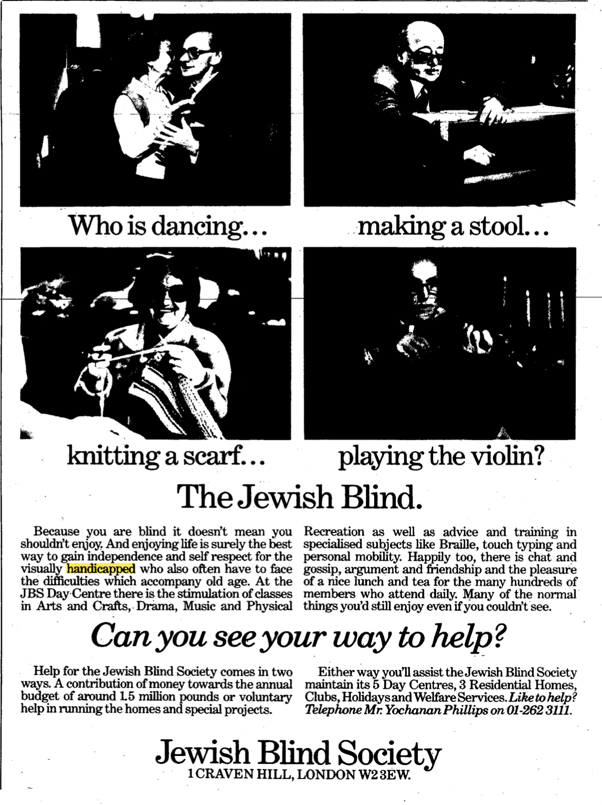

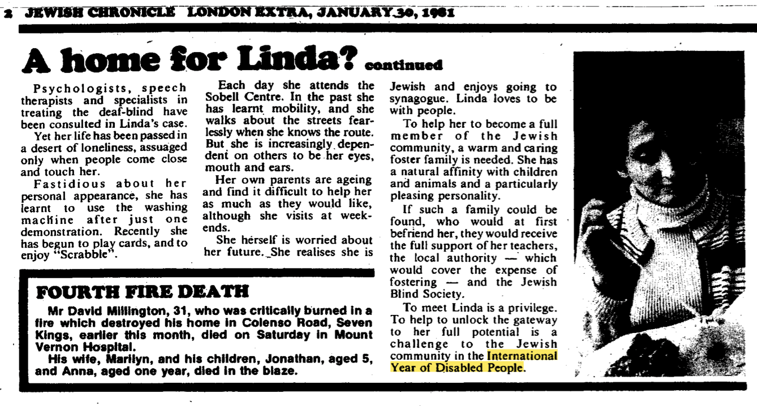

Other areas of Jewish life also were impacted by the message of 1981. Adverts in the Jewish Chronicle by charities like the Jewish Blind Society, for instance, were common, and by 1981 the specific message and brand of the IYDP was used to encourage awareness about disabled people. These efforts also included fundraisers, such as the performance of Barnum at the London Palladium in support of the Jewish Blind Society. This highlights the role of other Jewish organisations in spreading the message of the IYDP, and the importance of disabled organisations within specific communities to increase the IYDP’s impact.

As such, it is significant to consider intersectional aspects of the IYDP and recognize the impact the Year had across different communities. Without acknowledging barriers within specific communal contexts, a broad conceptualization of the impact of the Year cannot be understood. This logic is also in reference to the fact that Jewish efforts were seemly unrecognized at the time. For instance, no mention is made of any Jewish efforts in a pamphlet published in 1982 about the impact of the IYDP on Britain, and a section about religious life only details Christian efforts of inclusion and accessibility.[12] This underemphasizes the progress that was made by identifying the barriers disabled Jews faced and accounted for the uninformed mindset of the wider community, leading to issues such as that at the Egerton Road Synagogue. The IYDP presents a unique opportunity to explore a variety of intersectional disabled history, and future scholarship should aim to focus on this.

Visual sources are included with the permission of the Jewish Chronicle:

Jewish Chronicle, 1981, July 24th, p 19,

Jewish Chronicle, 1981, January 9th, p 5.

Jewish Chronicle, 1981, April 3rd, p 13.

Jewish Chronicle, 1981, January 30th, p 2.

Sources:

[1] Jewish Chronicle Online Archive, 1980, October 17th, p 39. Accessed here: https://www.thejc.com/archive/1.417622?type=edition&editionDate=1980-10-17&wholeEdition=true

[2] Jewish Chronicle Online Archive, 1980, October 31st, p 20. Accessed here: https://www.thejc.com/archive/1.417713?type=edition&editionDate=1980-10-31&wholeEdition=true

[3] Jewish Chronicle Online Archive, 1980, November 14th p 39. Accessed here: https://www.thejc.com/archive/1.190061?type=edition&editionDate=1980-11-14&wholeEdition=true

[4] Frankel, W, “Survey of Jewish Affairs, 1987”, (Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, Cranbury, 1988). p 239.

[5] Manchester Jewish Museum Oral Collection: JT41 – Paul Sutton

[6] Frankel, p 239.

[7] London Metropolitan Archives, ACC/2805/07/12/017 – ‘DISABLED PEOPLE: ‘REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS BY A SPECIAL SUB-COMMITTEE OF THE CENTRAL COUNCIL FOR JEWISH SOCIAL SERVICE’, PAPERS ON THE YEAR OF THE DISABLED AND CORRESPONDENCE WITH VARIOUS CHARITIES’

[8] London Metropolitan Archives, ACC/2805/07/12/017

[9] London Metropolitan Archives, ACC/2805/07/12/017

[10] London Metropolitan Archives, ACC/2805/07/12/017

[11] Jakobovits, I, “Dear Chief Rabbi: from the correspondence of Chief Rabbi Immanuel Jakobovits on matters of Jewish law, ethics, and contemporary issues, 1980-1990” (New York, KTAV Pub. House, 1995), p 134.

[12] Kates, H., Waller L., and Crampton, S., “International year of Disabled People … a beginning, not an end …” (London, National Council For Voluntary Organisations, 1982[?]), p 49.

Bibliography

- Hilary Kates, Linda Waller and Stephen Crampton, “International year of Disabled People … a beginning, not an end …” (London, National Council For Voluntary Organisations, 1982[?]).

- Immanuel Jakobovits, “Dear Chief Rabbi: from the correspondence of Chief Rabbi Immanuel Jakobovits on matters of Jewish law, ethics, and contemporary issues, 1980-1990” (New York, KTAV Pub. House, 1995).

- Jewish Chronicle Online Archive, 1980, October 17th, p 39. Accessed here: https://www.thejc.com/archive/1.417622?type=edition&editionDate=1980-10-17&wholeEdition=true

- Jewish Chronicle Online Archive, 1980, October 31st, p 20. Accessed here: https://www.thejc.com/archive/1.417713?type=edition&editionDate=1980-10-31&wholeEdition=true

- Jewish Chronicle Online Archive, 1980, November 14th p 39. Accessed here: https://www.thejc.com/archive/1.190061?type=edition&editionDate=1980-11-14&wholeEdition=true

- Jewish Chronicle Online Archive, 1981, January 9th. Accessed here: https://www.thejc.com/archive/1.387367?type=edition&editionDate=1981-01-09&wholeEdition=true

- Jewish Chronicle Online Archive, 1981, January 30th. Accessed here: https://www.thejc.com/archive/1.387492?type=edition&editionDate=1981-01-30&wholeEdition=true

- Jewish Chronicle Online Archive, 1981, April 3rd. Accessed here: https://www.thejc.com/archive/1.365336?type=edition&editionDate=1981-04-03&wholeEdition=true

- Jewish Chronicle Online Archive, 1981, July 24th. Accessed here: https://www.thejc.com/archive/1.225041?type=edition&editionDate=1981-07-24&wholeEdition=true

- London Metropolitan Archives, ACC/2805/07/12/017 – ‘DISABLED PEOPLE: ‘REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS BY A SPECIAL SUB-COMMITTEE OF THE CENTRAL COUNCIL FOR JEWISH SOCIAL SERVICE’, PAPERS ON THE YEAR OF THE DISABLED AND CORRESPONDENCE WITH VARIOUS CHARITIES’

- Manchester Jewish Museum Oral Collection: JT41 – Paul Sutton

- William Frankel, “Survey of Jewish Affairs, 1987”, (Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, Cranbury, 1988).