Malformed embryos in formalin, a school desk for wheelchair users at a former institution for intellectually disabled, and artfully staged portraits of people with Down syndrome dressed as kings, divas or superheroes: As diverse as the subject of disability can be, showing it in museums is generally considered a sensitive issue. During an archival field trip to Denmark and Sweden in December 2016 for my PhD research on Nordic disability history, visits to museums and archives of disability organisations not only provided me with additional insight into this little researched topic – they also show how histories of disability are being narrated to the broader public today. A foray through three exhibitions that span several centuries of medical, political and social response to disability in its various forms.

Part I: Human bodies in the service of science: ‘The Body Collected’ at the Medical Museion, Copenhagen

Two conjoined twins, meticulously divided into three parts – the skeletons, connected at the lower abdomen, the organs, and a stuffed taxidermy of the skin –, are put on display in a glass cabinet, surrounded by bones, foetuses and organs in jars. The description informs us that they were called Martha and Marie, born in 1848 to a poor working-class family in Copenhagen, and had died ten days later at the Danish Maternity and Nursing Foundation. What makes the visitor pause in morbid fascination is only one of many specimen in the exhibition ‘The Body Collected’ at the Medical Museion. The name reflects the programme: To trace the history of how medicine has collected, examined and used human tissue for the benefit of gaining knowledge about the human body and all that could ‘go wrong’ with it.

The conjoined twins Martha and Marie (1848) in the exhibition ‘The Body Collected’. All photos by Anna Derksen.

For this purpose the museum has opened its vast pathological collection, whose origins date back to the 18th century and the Danish doctor Matthias Saxtorph. Driven by the ideals of Enlightenment, Saxthorp tried to find the biological causes for congenital malformations and used the specimen to teach midwives and obstetricians long before the invention of ultrasound or x-rays. The shelves of jars containing healthy, malformed and diseased foetuses certainly arouse visitors’ emotions most strongly. But also the other exhibition parts contain expressive – gross, but beautifully displayed – samples that stimulate thought: about death and disease, physical (ab-)normality, and the ethical dimension of collecting and scientifically utilizing human remains.

Historically, medical examination had to begin with the whole body, before new scientific inventions allowed for smaller and smaller parts, such as organs, bones or slices of the brain. The setup of the exhibition mirrors this progress by combining historical developments with the concept of scale: “The human body has not just been anatomised – it has been atomised”, the exhibition catalogue explains. The breakthrough came with the invention of the electron microscope in the 1920s and 1930s, making it possible to see diseases invisible to the naked eye, for instance the structure of tissue and cells, blood and molecules.

A vitrine showing the effects of fractures and diseases on the human skeleton, bones and skulls.

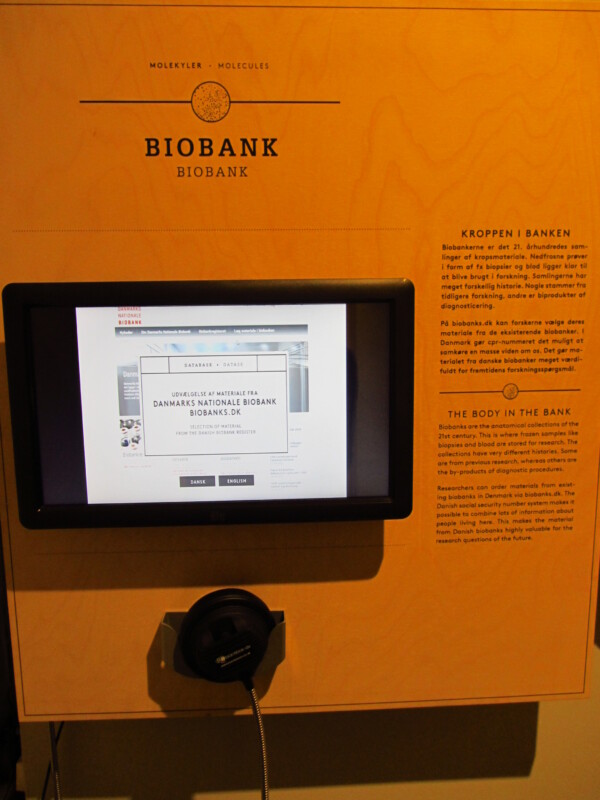

This takes us to the second part of the exhibition and the modern medical devices of today, in the form of human-genetic research. Denmark provides an interesting example, as it is one of only few countries in the world in which a blood test is taken from every new-born, screened for symptoms of diseases, and then stored at the Neonatal Screening Biobank. However, ethical ambiguities of human cell research – think for example of the Nordic countries’ long history of eugenics – are only implicitly present in ‘The Body Collected’. While some visitors might wish for more critical information, I think this is actually one of the show’s strengths: The concentration on the essential, in combination with the strong physical presence of the displayed objects, leaves room for associations and challenges us to find our own position.

Tendons of a hand, early 20th century.

As a disability historian, walking through the exhibition I could not help wondering about the individual people behind the specimen. ‘The Body Collected’ subtly highlights their de-humanization in the service of science. Treated as medical cases, their identities, life-courses and experiences were not deemed relevant. The exception are Martha and Marie, the conjoined twins, about which we know at least the names and social background, thanks to the doctor who recorded them. But de-humanization can also happen quite literally. This is shown, for example, by the formalin jars containing ‘little mermaids’, foetuses whose legs are fused together. The linguistic connection to fairy-tale creatures is obvious, implying that these foetuses do not belong to human kind but to a mythological species.

Computer simulation of Denmark’s National Biobank

To analyse causes for disease and disability, medical science has found it necessary to objectivize human body parts that were used by doctors, hospitals and research centres often without asking for consent of the patients or their relatives. Today, this fear is reined in by strict regulations and societal sensitivity, but the modern complexities of anatomic, pathological and genetic research make it continuously difficult to conciliate medicine’s pursuit of academic knowledge about the human body with the ethical questions concerning individual treatment – before and after death. The Medical Museion is to be commended for dealing with these questions over the broad time span of about 250 years, not only showcasing historical peculiarities, but hinting at current social debates as well.

Links and further readings:

- http://www.museion.ku.dk/bodycollected/

- http://creativedisturbance.org/podcast/heirloom-and-the-body-collected-as-seen-by-the-curators-meeting-with-louise-whiteley-and-malthe-bjerregaard/

- Knoeff, Rina; Zwijnenberg, Robert (eds.): The Fate of Anatomical Collections (= The History of Medicine in Context). Routledge, 2015.