In Norway the early 1980s marked a period of upheaval as various minority groups protested for political recognition. Between 1979 and 1982 the Sámi, an indigenous people from the northern parts of Norway, Sweden, Finland and the Russian Kola peninsula, tried to block the construction of a hydroelectric power plant at the river Alta in Northern Norway with mass demonstrations and hunger strikes. Although the protest itself was unsuccessful, it catapulted the requests of Sámi activists – indigenous environmental rights, land ownership and protection of language and culture – into the public and political spotlight. At the same time, another major protest was staged in 1981 by persons with disabilities, who used the celebration of the United Nations International Year of Disabled Persons as an opportunity to demand equality and participation in the welfare society.

Despite this simultaneity of events, however, one group curiously remained in the shadows: Sámi with disabilities. What did it mean to be a disabled Sámi in 1970s and 1980s Norway, a time in which both the disability movement and Sámi rights activism received hitherto unknown attention?

Sápmi, the territory of the Sámi in Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Norwegianization, special education and Sámi with disabilities

For centuries the Sámi had been the target of dominating measures by Nordic elites, from Christian missionary work to appropriation of land and programs of cultural assimilation. Extensive policies of ‘Norwegianization’ were adopted by the government in the mid-19th century. In an attempt to turn the supposedly primitive Sámi into Norwegian citizens, Sámi families had to give up the semi-nomadic lifestyle that followed the migration patterns of the reindeer, Sámi children were sent to boarding schools, and public use of the native language became suppressed. Until well into the 20th century the Sámi were regarded as inferior, categorized for example in the 1930 census together with “Kvens [a Finnish ethnic and linguistic minority], Citizens of other countries, the Blind, the Deaf-Mute, the Mentally Deficient, and the Mentally Ill”. The 1950 census no longer inquired after disabilities, but the Sámi remained grouped with foreign nationals and thus legally separated from other Norwegians – a status that was eventually changed, stimulated by the Alta protest, with the 1988 Amendment to the Constitution and the 1989 Sámi Act.

Special schools, health centers or support services were scarce in the north of Norway and seldom offered services in the Sámi language. Illustration from the Nordic seminar report “Disabled persons among national minorities and societies with limited resources”, 1981 (1982), p. 67.

For Sámi with disabilities the policy of Norwegianization had particular consequences. One was the lack of suitable services in the scarcely populated northern part of the country: While about 30.000 Sámi lived in Norway in 1980, no statistics were being kept about the prevalence of disabilities among this group, and little was known about indigenous views and approaches towards disabled persons. Recent studies by social scientist Line Melbøe suggest a more metaphorical understanding – a person with an intellectual disability could for instance be called somebody who ‘walks with a different rhythm than others’. In encounters with Norwegian doctors and authorities this could lead to severe communication problems, as Sámi were often unfamiliar with diagnostic terminology and care practices.

Another consequence was the absorption into the Norwegian system of care, rehabilitation and special education. For example, when blind or visually impaired Sámi children reached school age, their parents (like parents of non-indigenous children) could only choose between two public schools for the blind: Huseby blindeinstitutt in Oslo or Dalen blindeskole (from 1975 Tambartun blindeskole) in Trondheim, both hundreds of kilometers away. And while Sámi children since 1969 had a right to education in their native language, disabled Sámi at special schools still had to adapt to a purely Norwegian environment.

Disabled Sámi and the International Year of Disabled Persons 1981

During the International Year of Disabled Persons in 1981 the Nordic countries conducted a joint seminar on the topic of “Disabled persons among national minorities and societies with limited resources” in which the situation of Norwegian Sámi was discussed alongside that of Greenlanders, Åland islanders, and Swedish-speaking Finns. Bjørn Hansen, a representative of the Norwegian disability organization FFO (Funksjonshemmedes Fellesorganisasjon), gave a surprisingly self-critical perspective on the social status of disabled Sámi, denouncing the existing practices of care and special education as particularly harmful for personal development: “Because of the cultural differences, Sámi children will more easily be perceived as severely disabled in a Norwegian / Swedish / Finnish institution than in a Sámi one. As disabled persons in a foreign environment they will more easily develop a negative self-image.” Hansen expressed the concern that mental health issues among the Sámi were often a direct result of social prejudices and the policies of Norwegianization: “Being a Sámi brings with it great possibilities to also become labeled as disabled. Encounters with the majority population can have such a strong impact for many that they become disabled for life.”

The Huseby Educational Centre for the Visually Impaired in Oslo, here in 1953, also admitted Sámi children. In 1981 it started an initiative to develop a Sámi Braille alphabet in cooperation with the Nordic Sámi Institute and the Sámi Education Council. Photo credit: Oslo Museum, Leif Ørnelund.

In the end, however, results were few, with disabled Sámi not even mentioned in the final report of the International Year of Disabled Persons in Norway. Many important issues were ignored or at least not pursued further. Sámi identity was almost exclusively linked to the issue of language, cutting short discussions of accessibility to public services, the concerns of Sámi with other physical or intellectual disabilities, or prevalent social prejudices – against the Sámi as well as against disability in general.

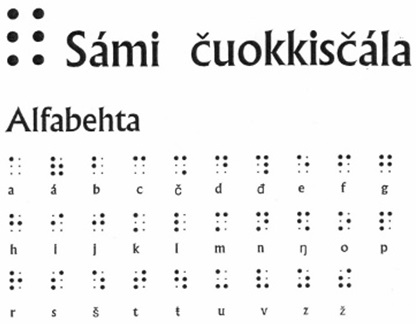

Apart from the discussions at the Nordic seminar, only a single project about the double minority situation of Sámi with disabilities is documented for the 1980s. Again this concerned special education: As material for Sámi with disabilities did not yet exist in their native language, the Nordic Sámi Institute in Kautokeino, the Sámi Education Council and Huseby blindeinstitutt in Oslo developed special braille letters for the Northern Sámi dialect (á, č, đ, ŋ, š, ŧ and ž) that could be added to the Norwegian braille alphabet. It was hoped that books translated into Sámi braille would enable visually impaired Sámi to finally make use of their right to education in their native tongue. While even today this is still far from a reality, at least a number of books has been published in Sámi using the special braille letters, with the Norwegian and Sámi cultural authorities aiming for more.

The Sámi braille alphabet developed in the 1980s. It is based on Norwegian (Scandinavian) braille with added letters used in the Northern Sámi dialect. Image by Tambartun blindeskole.

Concluding remarks

It took both public authorities and scholars a long time to turn their attention to the particular situation of Sámi with disabilities. It seems that Norwegianization policies and the country’s system of special education have led to a strict separation of Sámi and disability identities, despite the simultaneous protests of their respective rights movements. Melbøe et al (2016) come to a similar conclusion, pointing towards a “stronger emphasis on the battle for collective rights as a Sámi, compared with the battle for individual rights for people experiencing disability.” It is thus not only due to the scarcity of historical sources that these intersections are easily overlooked. While gender, class or race have become cherished cross-categories in the writing of disability histories, we should remind ourselves that there are more perspectives to consider – but also, that not all fit into popular narratives of emancipation and empowerment.

Sources and further readings:

- Bongo, Berit Andersdatter: “Samer snakker ikke om helse og sykdom”. Samisk forståelseshorisont og kommunikasjon om helse og sykdom. En kvalitativ undersøkelse i samisk kultur. Dissertation, Tromsø: Universitetet i Tromsø 2012. (PDF)

- Fjerde hefte: Samer og Kvener. Andre lands statsborgere. Blinde, døvstumme, åndssvake og sinnsyke, in: Folketellingen i Norge 1 Desember 1930, Oslo: Statistics Norway (1933), pp. 2-17. (PDF)

- Förbundet de Utvecklingsstördas Väl: Nordiskt seminarium om handikappade inom nationella minoriteter och inom samhällen med begränsade resurser, 20.-22.11.1981, Helsinki 1983.

- Hansen Blix, Bodil: Helse- og omsorgstjenester til den samiske befolkningen i Norge – en oppsummering av kunnskap. Omsorgsbiblioteket 2016. (PDF)

- Melbøe, Line: Identity construction of Sami people with disabilities, in: Global Media Journal, Australian Edition 12(1) (2018). (article)

- Melbøe, Line; Fedreheim, Gunn Elin; Opsal, Karin-Anne: Demokratisk deltakelse blant mennesker i en dobbel minoritetssituasjon som same og funksjonshemmet, in: Norsk statsvitenskapelig tidsskrift 33(3-4) (2017). (article)

- Melbøe, Line; Johnsen, Bjørn-Eirik; Fedreheim, Gunn Elin & Hansen, Ketil Lenert: Situasjonen til samer med funksjonsnedsettelser. Stockholm: Nordens Velferdssenter 2016. (PDF)

- Samisk skolehistorie 4, Karasjok: Davvi Girji 2010. Overview article on special education for Sámi with disabilities (in Norwegian, Sámi and English).

- Samisk skolehistorie 4, Karasjok: Davvi Girji 2010. Several articles on special education for Sámi with disabilities (in Norwegian and Sámi).

- Sørlie, Tore & Nergård, Jens-Ivar: Treatment Satisfaction and Recovery in Saami and Norwegian Patients Following Psychiatric Hospital Treatment: A Comparative Study, in: Transcultural Psychiatry 42(2) (2005), pp. 295-316. (article)

Thanks. Very interesting article!