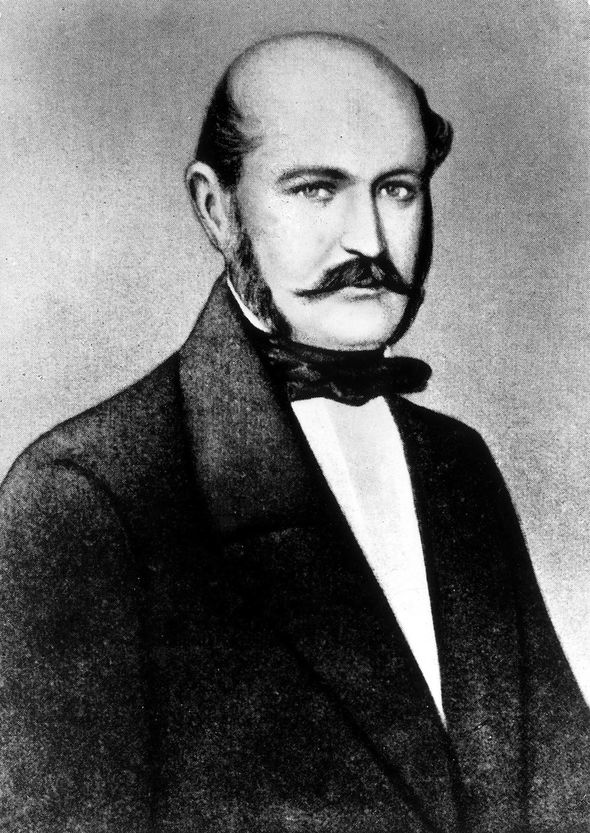

Last Friday Google Doodle paid tribute to the legacy of Ignaz Semmelweis (1818-1865), the Hungarian obstetrician who first discovered that handwashing can have a life-saving effect. In addition, Semmelweis was featured, if only briefly, in several leading media outlets such as CNN, Independent and Forbes. The charming and humorous figure wearing a bow tie that appears on google doodle, drawn on an authentic image of Semmelweis dating back to 1857, radiates optimism. This is no surprise: after all, his discovery symbolizes the power of science over ignorance. But there is another story here that went unrecognized in these brief tributes: Semmelweis’s tragic fate, which testifies to the arrogance of mainstream hierarchy vis-à-vis fresh insight coming from the margins.

A visualization of the handwashing technique of Hungarian doctor Ignaz Semmelweis (Hungarian: Semmelweis Ignác Fülöp, 1 July 1818 – 13 August 1865).

While working in the maternity wards of hospitals in Vienna and Pest (now Budapest) in the 1840s, Semmelweis became puzzled by a strange phenomenon. Mortality rates among expectant and new mothers caused by the infection that was then called “childbed fever” were generally high in this period. But they were much higher in the wards staffed by doctors than in those staffed by midwives. Semmelweis realized that this difference was due to the habit of doctors performing autopsies and examining women in the maternity wards without disinfecting their hands, a practice that was responsible for causing the infection. Having discovered that the deadly disease was passing from the bodies of the dead to healthy mothers on the unwashed hands of the doctors themselves, he instructed doctors to wash their hands with a chlorine solution between patients and especially after an autopsy. The result was instant: the mortality rate in the doctors’ ward dropped dramatically and was no longer higher than in the midwives’ ward.

Ignaz Semmelweis

Despite clear evidence – the method stopped the ongoing contamination of pregnant women – Semmelweis was not able to convince his peers about the effectivity of his simple solution. His stubbornly pursued hand-washing suggestions were rejected by his contemporaries who even mocked and stigmatized “the weird man.” Some doctors refused his idea on the grounds that a gentleman’s hands could not transmit disease. Importantly, Semmelweis’s method contradicted ruling theories of the age, for example, the one which held that miasma, or bad air, was responsible for spreading disease. It was not until Louis Pasteur’s arrival on the scene and the ensuing acceptance of germ theory that Semmelweis could be vindicated and retrospectively earned the title “the savior of mothers”. The rejection by colleagues which caused several avoidable deaths contributed to the deterioration of Semmelweis’s mental health: he started to behave strangely, gradually lost his sanity and in 1865 died alone and abused in a mental asylum in Vienna.

Semmelweis’s story inspired the concept called “Semmelweis effect” – the reflex-like rejection of evidence or novel knowledge which contradicts established norms, beliefs and paradigms. Moreover, his story not only inspired a new concept, but also innovative artistic work: Semmelweis, a song cycle by composer Raymond Lustig. The message of this music-theater work can be best summarized by directly quoting the composer’s website:

Semmelweis explores the theme that everything we think we know can be overturned violently, and asks what is it like to be the first to see into a terrible blind spot and perceive a truth too awful to believe? To be an “outsider”—a “foreign” doctor, Hungarian, but living and working in Vienna’s top hospital in a xenophobic era—and to fear that no one heard you, that the answer may die with you? To hold an earth-shattering insight, and yet be haunted by all the mothers that would not be saved.

It is evident that the sudden appearance of the coronavirus will forever change our societies as we have known them and that the global pandemic has brought us to a point of no return. At a time when researchers are feverishly trying to address a scientific void and racing to create a vaccine for a new disease, it is worth reminding ourselves that the solution will not necessarily arrive from where we expect them. Perhaps it will not be one of those star scientists or cherished research teams but a Semmelweis-like outcast who will provide a crucial clue. Perhaps the clue will be much simpler than expected. One cannot but agree with composer Ray Lustig that:

There has never been a more urgent moment in history to reflect on the mystery of insight, the tension between truth and hubris, our cultural myopia, and the clear truth that we, as individuals and as a society, need our “outsiders,” our fresh and brave ideas, literally to survive.[1]

A trailer of the play Semmelweis for which Ray Lustig composed the music. For more of his work visit his website http://raymondlustig.com/works/semmelweis/