As part of my RMa degree in Political Culture and National Identities I followed the course History of Human Rights last semester. In this course, given by Dr. Paul van Trigt, we set out to gain an understanding of human rights from a historical perspective.

What became especially clear in the course was the prominent position of one particular academic in the historiographical tradition of human rights: Yale historian Samuel Moyn. In his provocative book The Last Utopia: Human Rights in History Moyn seeks to challenge the prevalent notion of human rights as deeply rooted in history. According to Moyn, we can only speak of human rights in the way we currently understand them since the late 1970’s. It was at this moment that human rights – as a social movement based on an utopian idealism – came into existence. For Moyn human rights is then an utopian ideology based on internationalism; human rights as superseding the previously dominant notion of state sovereignty. Consequently, from this period onwards, the appeal to supranational institutions and their legal protections became essential.

To really appreciate Moyn’s intervention requires one to grasp the prevalent notion of human rights as something long-established, almost eternal. It is in fact not strange that this dehistoricization tends to take place with the concept of human rights, given that its philosophical appeal tends to lie in its timeless, universal and ahistorical character. However, the virtue of Moyn’s argument is that he unequivocally lays bare the reality of human rights as a concept that has been socially constructed in our very most recent history. Nonetheless, Moyn is not above criticism. Several authors have criticised Moyn, especially his argument that there was no such thing as human rights – as we know it nowadays – before the breakthrough in the 1970’s.[i]

My own contribution to the human rights debate has been to look at the role human rights played in the fight against apartheid. Specifically, to look at the way in which Oliver Tambo – who evolved into the most important spokesperson of the anti-apartheid struggle abroad – used the concept of human rights in his speeches to the United Nations. The case of South Africa is particularly interesting because of its time-span: the anti-apartheid struggle both includes the pre human rights boom era (as identified by Moyn) as well as the era after it. This is why a look at this case study has the potential to give credence to Moyn’s argument, at least if human rights in fact came to dominate the anti-apartheid movement in the 1970’s. This potential is something Moyn himself hints at.[ii]

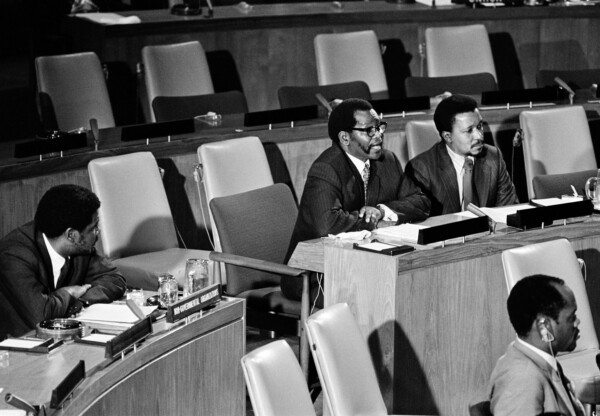

Oliver Tambo (centre) addressing the United Nations Political Committee against apartheid in 1973. [iii]

The four speeches that were the subject of my enquiry – given by Tambo in the period of 1968 until 1986 – were al given with the intent to apply pressure on the South African government.[iv] Making use of the international stage of the United Nations, Tambo used his rhetorical ability to highlight the crude racism that was at the core of the apartheid government. At the heart of all four appeals was a Manichean portrayal of the South African struggle: the ‘racist’, ‘colonial’, ‘fascist’ and ‘anti-human rights’ regime of South African versus the ‘multi-racial’, ‘anti-colonialist’, ‘anti-fascist’ and ‘pro-human rights’ resistance to apartheid.

All of these aforementioned concepts were employed by Tambo almost interchangeably; rather than showing ideological evolution, they should be viewed as different ways to describe an essentially unchanging struggle. This lack of change in Tambo’s speeches seems to partly challenge Moyn’s view of the 1970’s as the breakthrough of human rights as an internationalist utopia that filled the vacuum of other utopia’s losing their enchanting effects. For even in the speeches conducted after the 1970’s Tambo still talks about themes of anti-colonialism in relation to the struggle against apartheid. Although, admittedly, these appeals are simultaneously mixed with references to human rights.

Thus, my findings mainly work to muddle the water, challenging Moyn’s description of the radical occurrence of change; of the utopia of human rights replacing the utopia of anti-colonialism. These findings instead suggest that both the concept of human rights and that of anti-colonialism can fit together as ways of legitimising a struggle. However, it is important to realise that South Africa was in a sense a unique case. It was the last country in which a white minority ruled over a black population; a last residue of colonialism. Hence the anti-apartheid struggle might simply be an anomaly in Moyn’s thesis; the exception that proves the rule. Nonetheless, that does not mean that these findings are insignificant. It is also important to realise that not every case fits Moyn’s framework.

All of this, however, also hints at a critique at a conceptual level. Given that Moyn has chosen to adopt a clear definition of human rights, he easily discards things as “not being human rights”. Thus, even though someone might literally be using the words human rights, Moyn might assess this as in fact not actually being human rights. Although this strict definition has the virtue of clarity, I would argue that it does not always do justice to the complexity of the way in which different actors choose to employ the concept. Overall, this research mainly hints at the ambiguity and complexity of a concept such as human rights, and consequently emphasises the importance of understanding a concept and its development in its particular historical context.

[i]See for example: Roland Burke, Decolonization and the Evolution of International Human Rights (Philadelphia, Penn., 2010); Steven L.B. Jensen, The Making of International Human Rights. The 1960s, Decolonization and the Reconstruction of Global Values (New York, 2016).

[ii] Moyn, Last Utopia, p. 173.

[iii] T. Chen, UN photo (New York, April 1973) (http://africanactivist.msu.edu/image.php?objectid=32-131-512).

[iv] The speeches used are the following: Oliver Tambo, ‘Appeal for action to stop repression and trials in South Africa: Statement at the meeting of the Special Political Committee of the General Assembly [New York, October 8, 1963], in E.S. Reddy, Oliver Tambo: Apartheid and the International Community: Addresses to United Nations Committees and Conferences (New Delhi, 1991); Oliver Tambo, ‘United Nations must take action to destroy apartheid: Statement at the meeting of the Special Political Committee of the General Assembly [New York, October 29, 1963], in Reddy, Oliver Tambo; Oliver Tambo, ‘We Shall Win: Statement at the meeting of the Special Committee Against Apartheid’ [New York, March 21, 1978], in Reddy, Oliver Tambo; Oliver Tambo, ‘Victory is within our grasp: Statement at the World Conference on Sanctions against Racist South Africa’ [Paris, June 16, 1986], in Reddy, Oliver Tambo.